NCUA’s Hot Button: A Fresh View

By Dwight Johnston, Chief Economist, California and Nevada Credit Union Leagues

There is little doubt among credit union executives that the National Credit Union Administration’s “hot button” in examinations over the past few months is interest rate risk. Almost every credit union executive I have spoken with says NCUA examiners are on search-and-destroy missions.

Credit union managers opine how examiners walk through the door with pre-existing attitudes regarding “too much” interest rate risk, demanding to be shown otherwise. State-chartered credit unions have not experienced the same scrutiny.

Yes, examiners should be on the lookout for risks to balance sheets and weaknesses. Interest rate risk has always been on the agenda, but why is it now Public Enemy Number One? The obvious answer is rates are at or near historic lows, and NCUA fears a rise could damage credit union balance sheets.

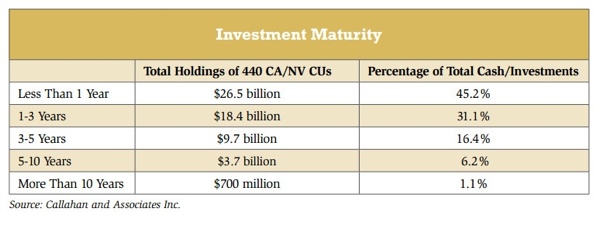

But how real are these worries? The “investment maturity” table I’ve attached is the maturity composition of investment portfolios for credit unions in California and Nevada. The less-than-one-year category accounts for 45.7 percent of portfolios, while 31 percent of investments are 1-3 years, 16 percent are 3-5 years, and less than 8 percent are more than 5 years. Certainly, there are credit unions having more risk than others—but overall, it’s obvious credit unions have little interest rate risk in investment portfolios.

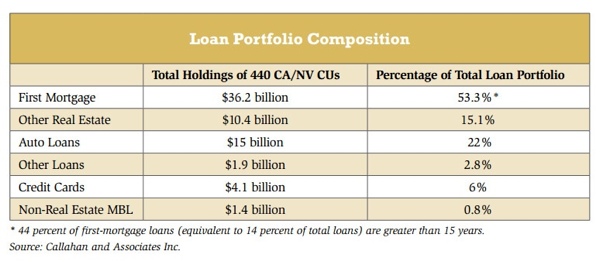

That means the grave risks lie in loan portfolios. The “loan portfolio composition” table shows that while there is some interest rate risk in auto loans, it is minimal given the average maturity of loans. Hence, the mortgage category is where you look for risk. We see that first-mortgage loans are 53.3 percent of total loans. But not all mortgage loans within credit union portfolios are 30-year fixed rate loans.

Breaking it down further, 44 percent of first-mortgage loans are greater than 15 years. This is the bottom line. The only arguably risky large asset class on credit union balance sheets, in terms of interest rates, is roughly 14 percent of total loans, plus total investments. Is this high risk, even when several credit unions’ capital ratios are at 10 percent? Perhaps there is an argument for credit risk or concentration, but not interest rate risk.

My point is not merely to question why examiners are zeroing in on interest rate risk, especially in investment portfolios. That’s irrelevant. However, it’s clear this is a focus of examinations, and you have to be prepared to deal with it. Many credit unions have systems in place to closely monitor and report interest rate risks, but others need to examine their systems to see if an upgrade is in order.

Credit unions should also review interest rate risk policies to see if there are holes or limits that need to be changed. The fact that examiners are focused on risk doesn’t mean you should respond by reducing risk, unless warranted. Just be ready to prove your risk is in line with policy and consistent with capital structure. The easy path is to reduce interest rate risk to minimal levels, but this would produce even narrower margins.

Interest rate risk is usually viewed from only one angle—rising rates. But credit unions should also view it from the perspective of even lower rates and/or a multi-year cycle of current rates. Minimal interest rate risk can be just as damaging as having too much risk when it comes to the long-term health of your credit union.