Alignment Matters

Since 1995 I have worked with hundreds of credit union leaders on various aspects of organizational strategy (thousands if you count conferences, schools, and workshops… but who’s counting?). Over that same time period my strategic recommendations have evolved. New regulations have been introduced, innovative technologies have come online, consumer demands have shifted. One recommendation, however, has never changed. No matter which direction a strategy takes you, everyone in the organization must be equally committed to execution in the context of the institution’s purpose as well as its strategic goals and objectives.

Of course many business books, blog posts, and business educators state similar opinions. My recommendation is not unique, so why, then, in the face of near universal advice to align the focus and effort of human resources around common objectives, do we see so many organizations give so little attention to alignment?

I think one key reason is that many leaders still do not believe that such alignment is all that necessary. I think they believe that some splintering in focus is okay because it won’t do any damage. Some have gone so far as to convince themselves that those with opinions contrary to the organization’s own provide a devil’s advocate viewpoint that may serve to keep the organization from making strategic mistakes.

I think this perspective is wrong.

Consider this story. It is all true…..

A single-sponsor credit union suffered two defined strategic challenges:

- It had fully tapped its sponsor, leading to limited opportunity for further growth;

- It had a severe lack of branch capacity, resulting in long lines of visibly frustrated members.

The credit union also had two distinct market advantages:

- It existed in a relatively peaceful market with few big-bank competitors;

- It had a sound reputation throughout the community – even as a single sponsor.

In response to its challenges and opportunities, it made two well-researched strategic decisions:

- It would open up its field of membership to the community;

- It would build a new state-of-the-art branch/main office.

The credit union also possessed a few other intangible assets, namely, a highly intelligent CEO with a community banking/credit union background, a committed and well-educated board, and a much-loved staff.

Despite what looks like the building blocks of an unqualified success story, I am guessing right now you are getting the sense that the soundtrack to this article should be the theme from Jaws.

The shark in the water was the misalignment between the institution’s key organizational functions: board, management, and staff. While board, management, and staff equally understood the credit union’s challenges and core competencies, and each understood and rallied behind the strategic solutions available to the credit union, each held uniquely different opinions about the purpose of the institution. The misalignment resulted in differing perspective with regard to the definition of successful execution.

I will share one anecdote that fully explains the dilemma.

Once everything was wrapped up… the branch built, the charter change approved, etc. … here’s what happened:

- Members waited in line less than they ever had;

- Membership growth resumed;

- Operational earnings and efficiency improved;

- The health of the credit union soared.

Here is also what happened:

- Rarely were members in a branch long enough to interact with one another. Members breezed through the branch because it was designed so that their time was not wasted standing in line. Most members were pleased with their new experience, though some long-time (more vocal) members did not like the efficiency because they spent less time with their friends (other members, employees).

- Board members rarely ran into throngs of members when they visited the branch. They began to feel like the institution was losing its close-knit, “everyone knows everyone” soul. Furthermore, board members were truly missing their opportunities to gain diverse member feedback. Rather than having a broad slice of members to query during any given branch visit they were left with feedback only from the dissatisfied. Their feedback pool was one-dimensional.

- Most employees liked the new branch and its built-in efficiency and extra capacity, but because serving members took less time, employees were being asked to fill their excess capacity with new tasks and responsibilities. Those dissatisfied with “extra” work were more diligent in communicating their displeasure. They began to feel, and share, the belief that they were being exploited.

- At the same time the credit union began performing well above the industry average in nearly every key category, management team members were being picked apart by board members and staff because, in the opinions of these more vocal people, the credit union was failing to truly serve its members, and the management team cared only about the “numbers.”

So, in the end…

- The CEO left;

- A board rift emerged;

- Changes began to be rolled back;

- Long-term board members chose not to be renominated to their positions;

- The institution’s leadership and culture changed substantially in less than a year.

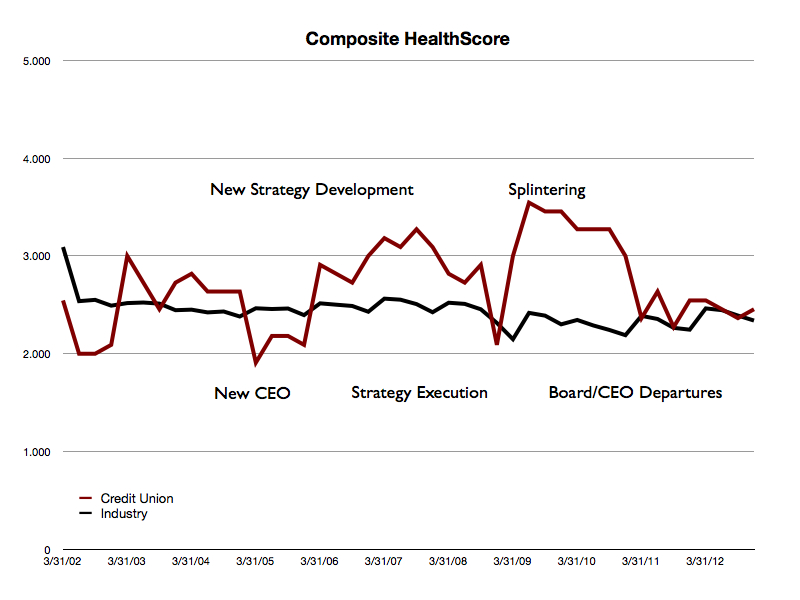

The chart above highlights the approximate timeframe of the points above in the context of the credit union’s HealthScore (along with comparison to the industry-wide HealthScore).1

Now I’ll point out that this credit union did not fail. It is still alive – but clearly its performance and health have fallen. Whereas once they were performing close to the 90th percentile of all credit unions, they now are clearly no better or worse than any other credit union. This should have been an incredible success story, but it wasn’t to be the case. The question to ask is, “Why?”

Making the right strategic decisions is critical to the success of any organization, but understanding why a strategic decision is made, and gaining institutional buy-in for the “why,” is equally as important. In this case, the question of institutional purpose was never fully addressed. Was the credit union to provide efficient, cost-effective service for members? Was it to be a place where everybody knows your name?

While these questions were discussed, a firm organizational commitment to a singular, defining purpose was never made. This left each group within the credit union, board, management, staff, and even members (not to mention individuals within each group), to interpret the credit union’s actions from the perspective of their own idea of purpose.

This credit union is certainly not unique. In fact, your credit union may be like them. One way to find out? Ask people why they think you are executing a particular strategy. Launching remote deposit capture? Bet some people think it is because you don’t want branch traffic, others because it makes it convenient for members, others because you want to attract younger members, still others because you want to trim your teller staff. Even if none of those are true, or they are all true, unless every reason for executing a strategy is both fully understood and supported, then you have misalignment as to institutional purpose, and misalignment leads to poorer performance.

Alignment matters… every day, regardless of the strategies you define or the tactics you adopt. To ignore it is to lead yourself into a no-win situation – and ultimately to poor organizational performance.

1: Glatt Consulting’s Credit Union Industry HealthScore is a composite financial performance score reflecting the overall financial health of US-based credit unions. The score range is based on a 5-point scale, with 5 being the most healthy and 0 being the least healthy. The HealthScore is calculated quarterly.