It’s that time of year again, when many of us pledge to live a healthier lifestyle. In order to do that, we need to plan our meals according to our appetite – not for how much we can eat, but for how much we should eat in order to avoid the consequences of overdoing it.

Likewise, to ensure the health of our credit union, we have to not only assess and measure the amount of risk we take, we have to know how much risk we’re willing to take in the first place. In other words, what is our appetite for risk?

Risk appetite is the amount of risk we’re willing to accept in pursuit of our strategic objectives. Assessing risk appetite is a critical first step that will guide our enterprise risk management (ERM) and strategic planning efforts at a broad level, and our daily activity at a more narrow level. Our appetite for risk will shape our decisions and actions, align organizational performance, and identify inconsistencies within our decisions and actions.

By its nature, risk appetite is strategic, while risk tolerance – the application of our risk appetite to our operations – is tactical. Risk tolerance is generally stated in terms of the metrics we use to measure performance, as either a specific target level or a range of acceptable outcomes. For example, if part of our risk appetite is a general unwillingness to let capital levels fall below targeted levels, even temporarily, we might see a relatively high minimum threshold, or a tight range, for our net worth ratio. The cost of that will probably be some foregone strategic opportunities that would require capital investments, but it’s important to be true to our risk appetite.

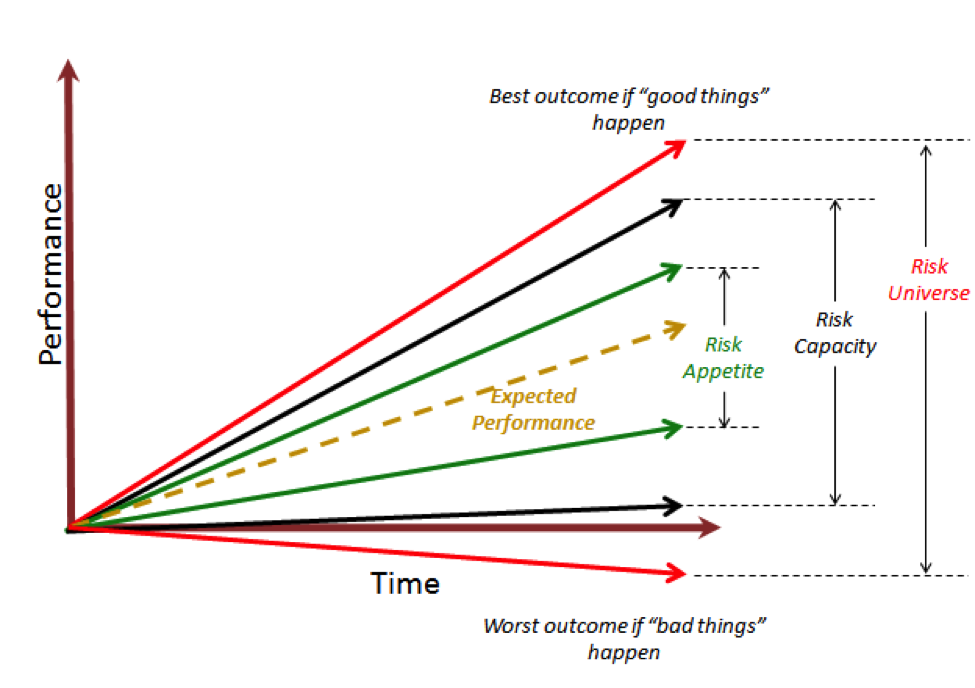

Figure 1 below illustrates risk appetite within the broader context of the universe of all possible risks, and our capacity for risk, which is a function of our capital and the regulatory landscape. As a credit union, there are some risks we simply can’t take, so our risk capacity is narrower than the risk universe. However, there are some risks that we could take that we might not want to take. That attitude toward risk defines our risk appetite, which will be narrower still than our risk capacity. Note also that by avoiding a certain level of negative outcomes, we give up some level of positive outcomes; such is the nature of the risk/return tradeoff.

How do we apply risk appetite in a strategic planning context? First, let’s consider the typical outcome of the planning exercise. We begin with where we are today, and we cast a vision for where we want to be at some point in the future. Then, we need to create a “road map” of how we’re going to get there: our strategic objectives. Risk appetite provides the boundaries of that road. If the things we’d need to do to achieve our objectives would violate our risk appetite, we need to either re-think where we want to be in the future, or come up with a way to get there that won’t fall outside our appetite for risk.

Given that risk appetite guides our organizational performance, then, how do we assess it in the first place? We at The Rochdale Group conduct an online survey of management and the board, asking 22 questions across five general areas of a credit union’s operations. Each question assesses the respondent’s willingness to assume risk by doing a certain thing within each of those areas. The response is based on a scale from one to ten, with one representing a strong unwillingness to assume risk, a ten indicating a strong commitment to assume risk, and a five indicating an average willingness to assume risk for each question. The surveys are typically anonymous, but each group (management or board) is identified.

Armed with the results, we graph the distribution of responses to each question from each of the two groups – management or board – showing the mean and plus or minus one standard deviation. Then we line up the management and board graphs for each question to identify the degree to which the two groups are aligned in their attitudes toward risk. In some cases, the alignment is very strong, and in others, there is greater variation between management’s and the board’s risk appetite, but common ground can typically be identified as we facilitate a discussion of the results.

Finally, we draft a series of risk appetite statements for each of the five areas covered under the survey that describe, in general terms, how much risk the credit union is willing to take in that area, guided by the questions asked. These statements are strategic in focus; think of them as mission statements for risk. Those statements will then drive the metrics we select for each of those areas as risk tolerances, to ensure that we don’t violate our risk appetite.

It’s critical to engage the board in this exercise. Using an analogy similar to our strategic “roadmap” discussed earlier, the board’s job is to place the curbs on the track, while management’s job is to run the race. And the value of the exercise is obvious: as executives, we want to know whether our board is highly risk-averse, or more aggressive in their willingness to assume risk. And directors should want to know whether they’re potentially holding the credit union back, or whether management is. Both groups will be interested to see how well aligned they are (or not!). We typically find that the strongest alignment is found in credit unions whose management has already done a thorough job of educating the board regarding risk.

A few important considerations are in order. First and foremost, risk is not a bad thing for credit unions. We are in the risk-taking business. By definition, as financial intermediaries, our role is to intermediate risks on behalf of our members that they themselves are unwilling or unable to take. If we don’t do that, we don’t bring value to our members. The key is to know how much risk we’re willing to assume in the pursuit of serving them.

Second, it’s important to re-visit risk appetite periodically. We recommend the appetite statements be reviewed annually, preferably at the beginning of each strategic planning session, and that they be validated or revised as appropriate. It isn’t necessary to repeat the survey process more than about every three years.

Finally, while the risk appetite may change as market conditions, the regulatory landscape, the composition of the board, or of management undergo changes, we must avoid “appetite creep.” This occurs when we change the risk appetite (usually toward a greater willingness to assume risk) because we’re approaching the limit of the risk tolerance used to ensure we don’t violate that aspect of our risk appetite. For example, we might have a limit on the amount of mortgage risk we’re willing to assume, measured using an upper limit of 600% of capital in first mortgage loans and mortgage-backed securities. If we move that limit to 700% just because the actual ratio hit 590% and we want to keep making mortgage loans, that’s appetite creep.

A person trying to eat healthy must first and foremost understand his or her appetite, in terms of what they can eat in order to attain their health goals, vs. what they’d like to eat. Likewise, credit unions must understand their risk appetite before engaging in the risk-taking activities that define their purpose in serving their members. Total risk-aversion is neither possible nor strategically sound for credit unions, but neither is gluttony advisable. As a former colleague once said, “The greedy become the needy.”

For more information regarding risk appetite assessment, please contact the author at bhague@rochdalegroup.com or 913.890.8022.