Don’t lower loan rates quite yet

Yes, interest rates across the yield curve are down, but does that mean loan rates should follow suit? Maybe not quite yet.

If the last couple of years have taught depositories anything, it’s that liquidity and the stickiness of deposits can change quickly. Balance sheets grew tremendously from 2020 through 2021, and financial institutions had more cash than they knew what to do with at that time. As inflation ticked higher and higher, the Fed took steps to combat this by beginning to raise rates in March 2022. By the end of 2022, the Fed had raised rates 425bps and the 2yr, 5yr, and 10yr points on the curve had increased over 360bps, 250bps, and 210bps, respectively.

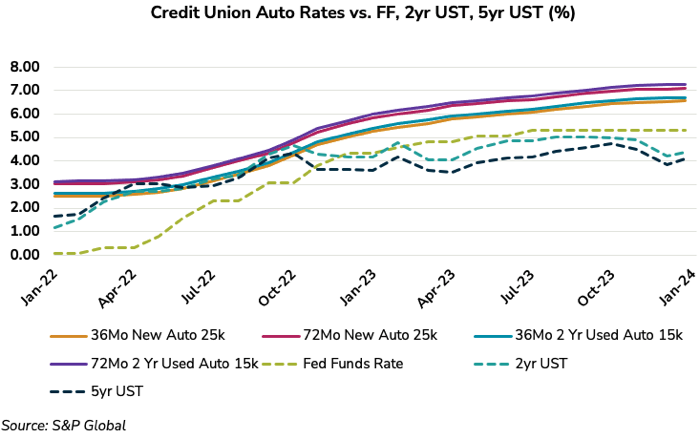

Credit unions were slow to adapt, as we can see from the figure below.

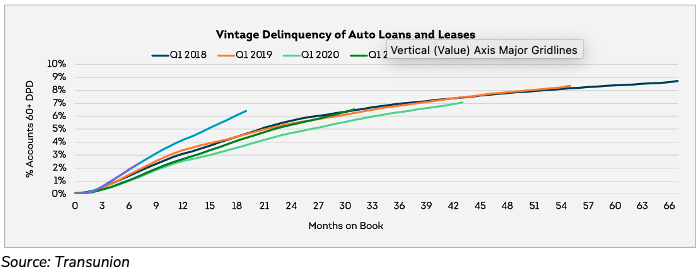

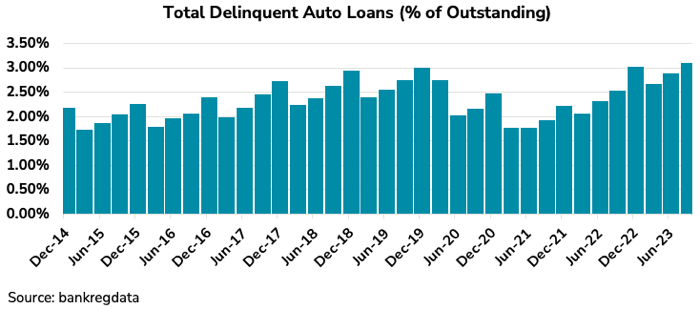

Considering where the delinquency rates for auto loans and leases are today, it’s clear that those originated in 2022 are increasing at a faster rate than older vintages. This is where institutions should ask themselves, was default risk appropriately priced into these loans at origination?

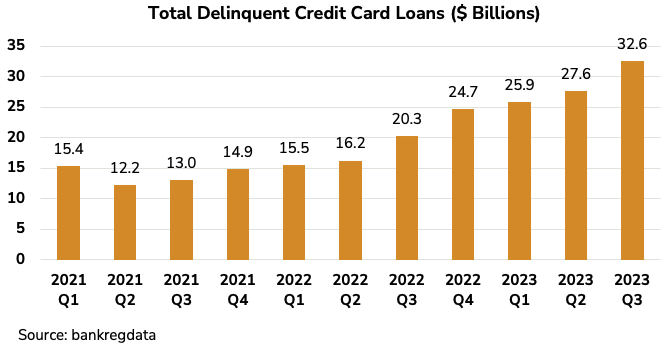

Depositories need to be very selective about the assets they are adding to the balance sheet right now given credit concerns and current cost of funding. It’s imperative to keep some form of margin going in a year where earnings look bleak for most financial institutions.

If your institution wasn’t the first to increase its loan rates, then why be the first to lower them? Doing so could voluntarily compress margins at the expense of profits, reducing returns to key stakeholders. To decrease rates now implies that loans rates were already raised sufficiently to price in a fair/appropriate risk spread. If a high enough risk premium has not yet been achieved relative to alternative investment options, then financial institutions may still need to raise rates further, rather than lower them.

Let’s go back to the fundamentals of finance and break down exactly what an interest rate is.

Nominal risk-free rate (two-year UST for example) = real risk-free rate (theoretical rate without inflation premium) + expected inflation rate (self-explanatory)

Loan rates are built off the nominal risk-free rate by adding in premiums associated with the risks of lending to consumers in different economic and credit cycles.

Default risk/credit risk

This is a premium that has been increasing over the past year due to rising delinquencies across most consumer lending as seen above. This is reflected in CECL numbers each quarter. Some loans will carry a higher weighting for this associated risk compared to others, but nevertheless, all loans will carry this risk. Pricing managers should be adjusting this premium upward given the rise in delinquencies. Data shows, that many have not quite compensated themselves fairly for this risk on their balance sheets. Originating loans at high LTVs in early 2022 when collateral values were at a significant risk of declining was not in the best interest of depositories, as they now have to hold reserves against these higher LTV lower valued collateral loans.

Liquidity risk

Not all loans have a transparent and observable market. Therefore, the ambiguity surrounding that lack of transparency should be added into the loan rates offered to consumers to compensate financial institutions for the risk of receiving less than fair value for the loan if they need to sell (even if your depository doesn’t think it will need to sell in the future). As with default risk, some loans will carry a higher weighting for this associated risk compared to others.

Duration risk

The longer a loan is outstanding, the more price volatility it will experience. Rates should adjust upward to reflect the risk associated with tying up funds for longer periods of time.

Options risk

With mortgage loans, underlying borrowers have the option to prepay on their loans without penalty leading to uncertainty surrounding future cash flows. Lenders sell this right to the borrower when originating the loan. As rates fall, this option becomes more valuable to the borrower and drives cash flow contraction and heightened reinvestment risk. Calculating this risk premium into the loan rate at origination is imperative to profitability for the institution.

So, what exactly is a loan rate? It’s a rate the lender is willing to accept given the encompassing risks of a particular borrower during a particular market. Depositories should lend where they can be rewarded for the risks associated with lending in the current market.

Current Market Loan Rate = Current Market Nominal Risk-Free Rate + Current Market Default Risk Premium + Current Market Liquidity Risk Premium + Current Market Duration Risk Premium + Current Market Options Risk Premium

The Treasury benchmark for each loan should be a baseline for a financial institution’s loan rates, but not a determinant on how much to move rates up/down. That adjustment up/down should be a reflection of the risk associated with lending during that cycle. Throughout economic and credit cycles (which seem to be diverging currently), the types of risk associated with lending will remain the same, but their weightings within the rate offered to borrowers will change.

So, why leave rates where they are when the two-year rate is down? Or maybe even consider adjusting them higher? Because the Nominal Risk-Free Rate is exactly that; Risk-Free. The rates institutions offer to borrowers come with risk premiums the federal government doesn’t have to pay.

Many auto lenders did an average to poor job of adjusting baseline auto loan rates and frequently miscalculated risk premiums during the 2022-2023 interest rate cycle. The prioritization of gaining market share through exceedingly competitive rate-setting was often achieved at the expense of liquidity and return on capital. Even with liquidity returning to many balance sheets, we anticipate margins will remain tight throughout 2024. It’s important to be selective about what financial institutions add to their balance sheets and evaluate capital allocations on a risk-adjusted basis. Now is the time to learn from 2022-2023 decisions and not be so quick to hit repeat.

Co-author: Gabby Kisber, Director, Advisory Services